Squat Lobster

Author and Illustrator: Winifred Niedjalski

Photos: Thank you to Andy Murch for the use of his Photos.

Common Name: Squat Lobster

Scientific name: Munida quadrispina

Length: Squat Lobsters range in size from one inch to four inches. Their carapace reaches up to 2.6 inches long, and their legs may be several times longer.

Identification:

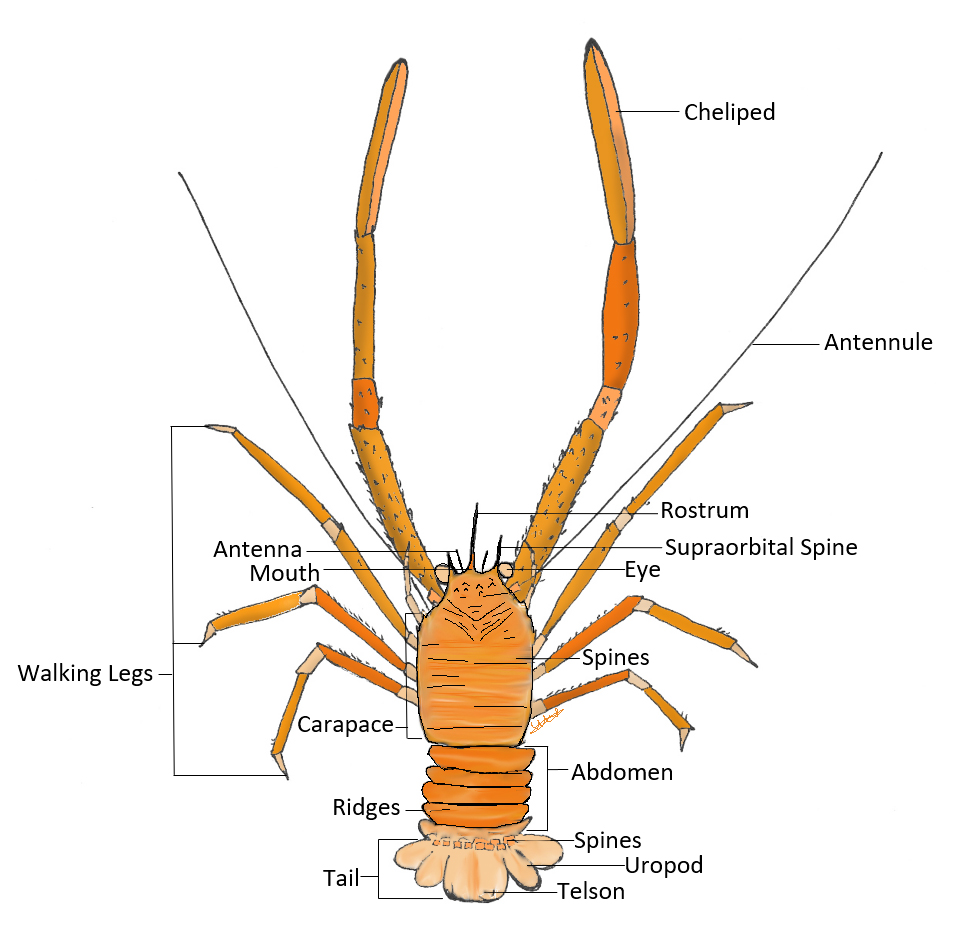

- Legs: Squat Lobsters have ten legs, which vary in size. The first pair is small and primarily used to clean the gills. The second pair is the thickest and longest, containing claws for defence and cleaning. The remaining three pairs are slender and used solely for waking.

- Carapace: The carapace is lined with small spines and functions as a protective cover for the Squat Lobsters to protect the internal organs. The carapace has greater length than width and is a crucial aspect of structural support.

- Abdomen: The abdomen is located behind the carapace and tends to be more flexible, with no spines but a few ridges. Inside the abdomen, the Squat Lobster stores its tail.

- Tail: Squat Lobsters have a well developed tail located under a groove in their abdomen. The tail is fan-shaped and is used to swim backwards as a defensive mechanism.

- Coloration: The Squat Lobster is primarily a mix of red and orange. Its central portions of the body, the carapace and abdomen, are red-brown with a lighter ventral of red ridges and white grooves. More specifically, the Squat Lobster has blue spots along the cervical groove, which allows it to stand out among other lobster species. As for its legs, its chelipeds are red with white tips, and its walking legs have white bands progressing down the leg. Their tail is a light translucent orange.

Habitat The Squat Lobster is found worldwide, living in global oceans except for the cold Arctic and Antarctic waters. The species Munida quadraspina is located in Pacific Northwest waters from Alaska to California. In British Columbia, they are commonly observed at Cape Beale, Vancouver Island, but are known to be located up the coast.

Generally, Squat Lobsters live in 12-1463 metres depts on graves, mud, and rocky faces. Throughout British Columbia, they populate the surfaces of deep-sea sponges, where there is a low current.

Prey Squat Lobsters are opportunistic feeders, meaning they consume various organisms depending on availability and habitat. They scavenge their location by excavating muddy or sandy deposits to sort for edible components with their mouths. In addition, they also prey on larger animals. Some of the organisms and animals they feed on include:

- Shrimp: Squat Lobsters consume benthic shrimp, disturbing both human shrimp traps and the shrimp ecosystem.

- Detritus: A primary food source for the Squat Lobster is detritus, which is dead plant and animal matter.

- Small Invertebrates: In addition to shrimp, Squat Lobsters have been observed preying on other small invertebrates, especially crustaceans local to the specific habitat.

- Organic Particles: Squat Lobsters feed on organic particles found on the seafloor. Like detritus, organic particles contain dead plant and animal matter, but living organisms and other organic materials are also present.

Predators The Squat Lobster is an essential aspect of the marine ecosystem, being prey for many organisms, including:

- Fish: From juvenile to adult fish, many fish species are common predators of Squat Lobsters. In BC, fish such as cod, haddock, and striped bass pose a significant threat to the individual Squat Lobster.

- Large Marine Mammals: Depending on the location, marine mammals such as whales, dolphins, sea lions, and sea otters feast on Squat Lobsters. In BC, sea otters, sea lions, and seals are marine mammals most likely to eat the population.

- Marine Birds: Seabirds may forage Squat Lobsters near the surface as part of their diet.

- Crustaceans and Mollusks: Certain mollusks, such as Octopus and Squid, feed on Squat Lobsters, as well as crustaceans, such as Crabs.

Life Cycle The life cycle of the Squat Lobster is similar to other crustaceans but contains some critical differences throughout the stages:

- Eggs: It commences with the female laying eggs attached to her abdomen.

- Zoea Larvae: As the eggs hatch, the larvae are planktonic and drift freely in the water. The progression from this stage to the next is significantly shorter than other crustaceans, lasting only a few days.

- Megalopa Larvae: After multiple transformations, the larva transforms into megalopa larvae, the lost developed and defined stage.

- Juvenile: The megalopa larvae metamorphose into a juvenile Squat Lobster, where it now becomes benthic, settling at the bottom of the ocean.

- Adult: In the final stage, the juvenile Squat Lobster grows into their distinct body shape and proceeds to live as an Adult Squat Lobster.

As for timing, the Squat Lobster Munida quadrispina’s life cycle is poorly studied. However, a detailed study of M. subugosa, a species located in Argentinian waters, was observed to have a reproductive cycle starting in May and ending in September, just in time to line up with the autumn zooplankton blooms. If basing the cycle on the influence of blooms, it could be hypothesized that Munida quadrispina would follow the same schedule, starting with egg development in females during May and ending with larvae hatching in September.

Fun Facts:

Squat Lobsters currently contain 60 genera and over 900 species, with an estimated 120 species yet to be discovered.

To obtain food, Squat Lobsters sometimes steal food from sea anemones.

Unlike crustaceans who cannot swim and walk along the ocean floor, Squat Lobsters can swim actively.

For defense, Squat Lobsters squeeze themselves between rocks, allowing them to defend with their large claws while keeping a defensive position.

References:

Aquarium of the Pacific. (n.d.). Squat lobster. Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/squat_lobster#:~:text=Squat%20lobsters%20resemble%20lobsters%20in,pair%20has%20very%20small%20claws.

Baldwin, A. (2021). INFRAORDER ANOMURA (MOLE CRABS, HERMIT CRABS, KING CRABS, PORCELAIN CRABS, AND SQUAT LOBSTERS) OF BRITISH COLUMBIA. Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://ibis.geog.ubc.ca/biodiversity/efauna/AnomuraMoleCrabsHermitCrabsKingCrabsPorcelainCrabsandSquatLobstersofBC.html

BudSquat Lobster. (2023, September 11). Squat Lobster, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Squat Lobster. Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://gohiking.ca/squat-lobster/

Cowles, D. (2005). Munida quadrispina Benedict, 1902. Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://inverts.wallawalla.edu/Arthropoda/Crustacea/Malacostraca/Eumalacostraca/Eucarida/Decapoda/Anomura/Family_Galatheidae/Munida_quadrispina.html

Hart, J. (2021). Fauna BC: Electronic atlas of the wildlife of British Columbia. Retrieved January 22, 2024 from https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Munida+quadrispina

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!