Thresher shark

Author: Keira Lane

Photo: Thomas Alexander

Common name: Common thresher shark, Atlantic thresher shark

Scientific name: Alopias vulpinus

Size range: The common thresher shark is the largest species of thresher shark in the world and in Canadian waters they are generally between 3.3 to 5.5 meters (10.8 to 18 feet) in length, though some can be up to 6.1 meters (20ft) in length.

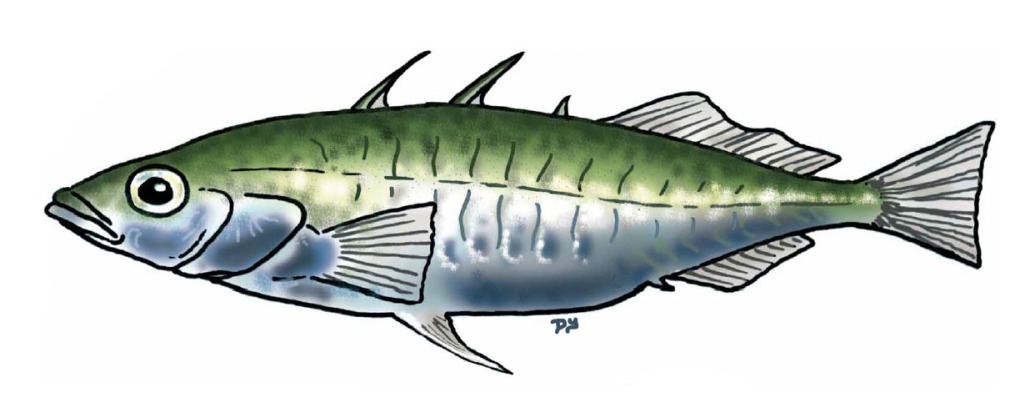

Identifying features: The common thresher sharks have a short dorsal fin and an enormous upper caudal fin that’s 50 percent of the total length of the shark. They have a short snout with large eyes placed forward on the head. They also have relatively small teeth in their jaws for a shark. There are 3 types of thresher sharks, common thresher, pelagic thresher, and the bigeye thresher. Depending on the type of thresher shark they can be gray, blue, brown, or purplish in colour. The common thresher shark is a dark bluish-grey on top with a metallic reflection on their side. The dorsal and pectoral fin has an extended dark coloration.

Habitat: The common thresher shark can be found in all of the warm and temperate oceans of the world. On the Pacific coast it is found from British Columbia, Canada to Oregon in the US. They mostly swim at the surface of the continental shelf but they can also occur at depths of 1,200 feet or more. Younger common thresher sharks can be found in shallower waters and like jumping out of the water, a behavior called breaching. The adults migrate seasonally with the males traveling farther northwards and reaching the coast of British Columbia in the late summer. The common thresher sharks must keep swimming so that water flowing over their gills will oxygenate their blood.

Food/Prey: The common thresher shark is a predator of fish. They are solitary creatures and usually never hunt in groups. They mainly feed on schooling fish, cephalopods, squids, crustaceans and sometimes seabirds. They splash the water to frighten them forcing fish to form tighter schools. Sometimes they use their long tails to stun their prey. The marine animals that are most likely to prey on the thresher sharks are Killer whales and larger sharks. The thresher shark isn’t dangerous to humans but can cause damage to fishing gear. .

Life Cycle: Thresher sharks can live up to at least 19 years old and mature in 3 to 8 years. The females are ovoviviparous and give live birth to 2 to 6 pups that are around 1.5 metes (5 feet) in length. Due to the long time it takes for maturity the thresher shark is at risk of being overfished.

References:

De Maddalena, A., Preti, A., & Polansky, T. (2007). Sharks of the Pacific Northwest: Including Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and Alaska. Harbour Pub.

Hart, J. L. (1973). Pacific fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada.

(2019, January 30). Thresher shark. Retrieved January 19, 2024, from https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/profiles-profils/threshershark-renardmarin-atl-eng.html#