Yellow Shore Crab

Scientific name: Hemigrapsus oregonensis

Author: Noah Stewart

Photos: D. Young

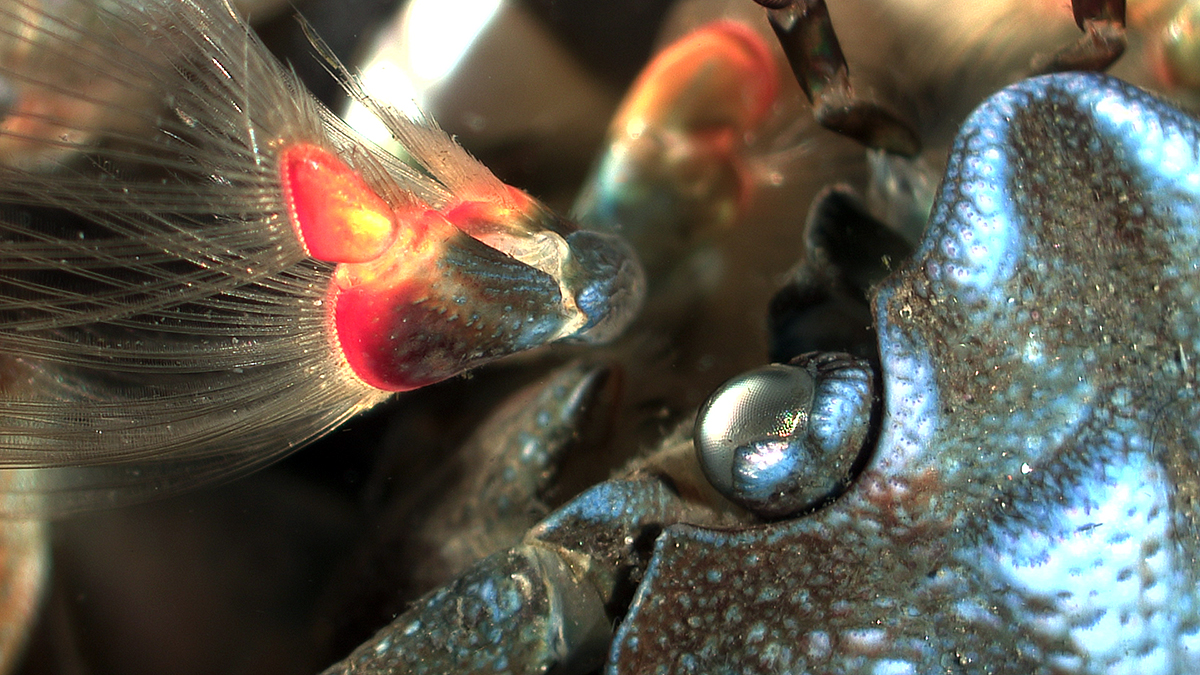

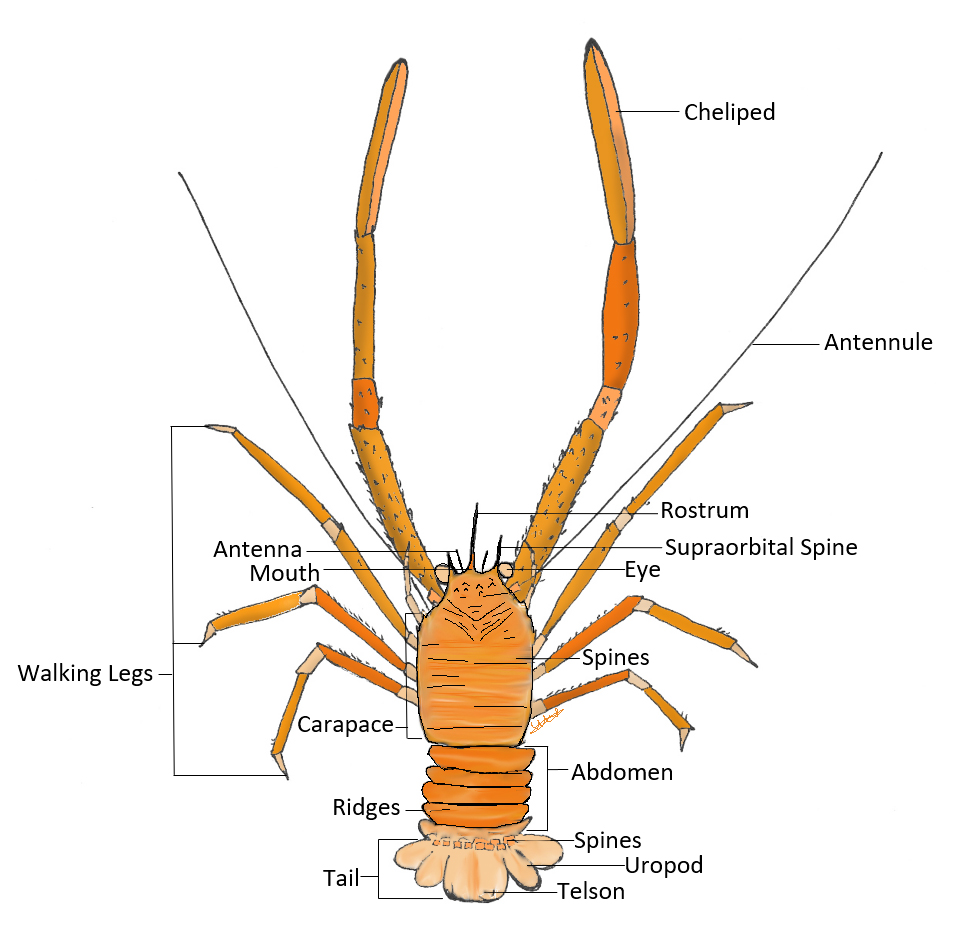

Identifying features The Yellow Shore Crab is characterized by its distinctive yellow to grey-green colouration though the the younger ones are commonly white with a mottled green pattern. They also may appear rarely as a purple morph. They can be as large as 49.5mm (1.9 inches) but are generally less than 42mm (1 inch). They have a line of hairs (setae) on their legs which help distinguish them from their twin the Purple Shore Crab (Hemigrapsus nudus) which lacks hair.

Habitat This is the most commonly seen crab in the Pacific Northwest. It lives in intertidal zones under rocks but is also found around sandy shorelines and in mud flats, eelgrass beds and estuaries. In mud flats it often uses the burrows made by mud shrimp. It is often found in the same place as the Purple Shore Crab (H. nudus) but has a preference for areas with lots of plant matter and slower currents.

Diet They tend to not be picky when it comes to diet as they are more of the scavenger omnivore. They will mostly feed on microorganisms such as algae and diatoms and will occasionally eat small invertebrates if they are able to. They are also able to filter feed.

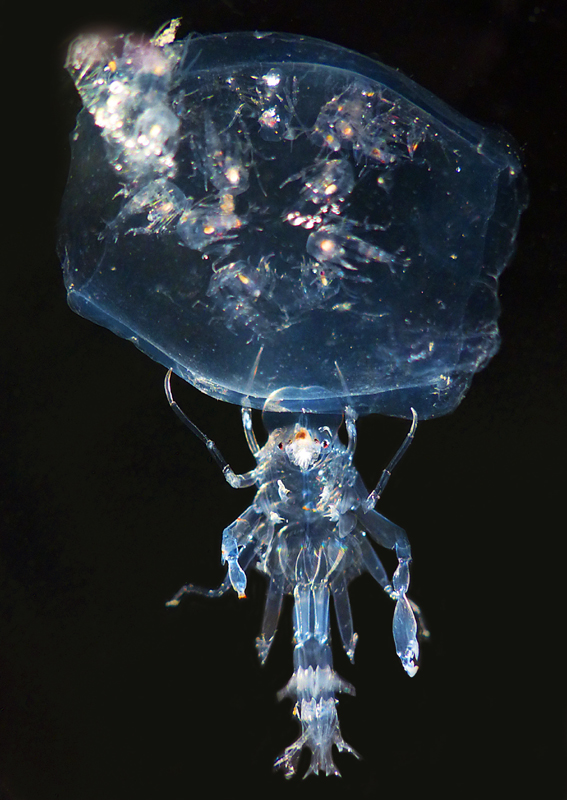

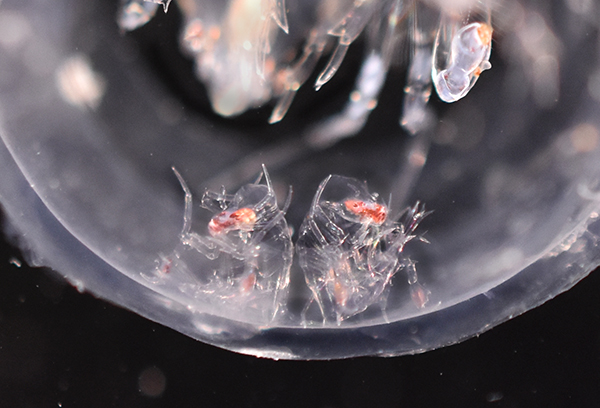

Reproduction Its breeding season is usually concentrated in the earlier months of the year from around February to May and hatching will then occur in July. Also occasionally, there will be a second breeding season that would begin in August and with hatching occurring in September. It has the typical crustacean life cycle having the egg, zoea, megalops then adult stage like most crabs.

Fun Facts

- It is capable of resisting hypoxic conditions unlike many other shore crabs

- Feeds mainly at night

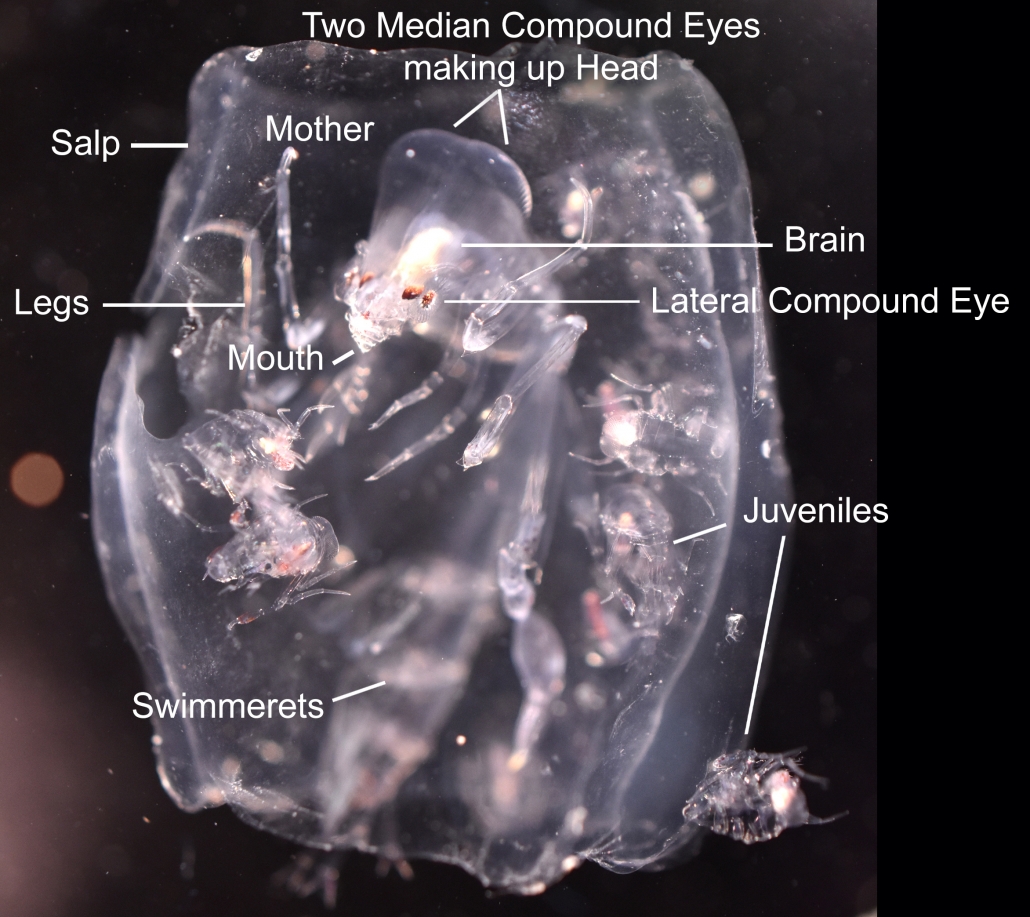

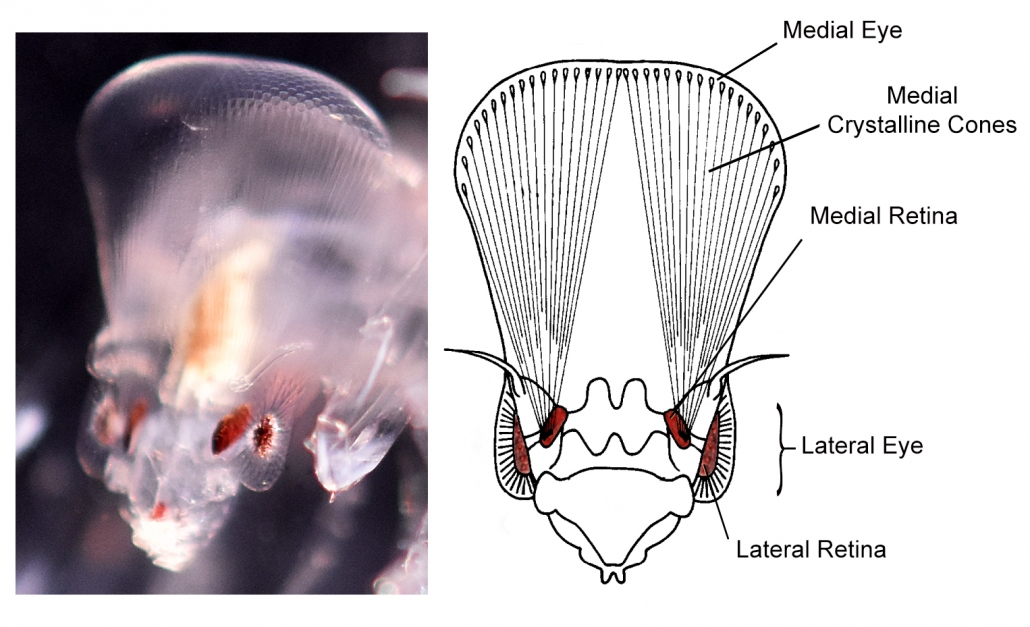

- Occasionally has a parasitic isopod in its perivisceral cavity but can’t be seen by the naked eye

References

(2017, November 9). YouTube: Home. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://inverts.wallawalla.edu/Arthropoda/Crustacea/Malacostraca/Eumalacostraca/Eucarida/Decapoda/Brachyura/Family_Grapsidae/Hemigrapsus_oregonensis.

Jensen, G. C. (2014). Crabs and Shrimps of the Pacific Coast: A Guide to Shallow-water Decapods from Southeastern Alaska to the Mexican Border. MolaMarine.

Rafter, M. (n.d.). Yellow Shore Crab (Marine Species of Crab Cove (Alameda, CA)) · iNaturalist. iNaturalist. Retrieved January 26, 2024, from https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/181284

Sept, J. D. (2019). The New Beachcomber’s Guide to the Pacific Northwest. Harbour Publishing Company Limited.